Hamlet's Mill: Myth, Ancient Science, and the Secret of Heavens

1. Introduction: A Mill That Grinds Time

Have you ever wondered if the stories of gods, heroes, and catastrophes of ancient cultures, from Hamlet to Noah, are more than just legends? What if they were actually a scientific manual, written thousands of years ago, describing the cycles of the universe?

In 1969, historians Giorgio de Santillana and Hertha von Dechend presented a revolutionary theory in their book "Hamlet's Mill." They challenged everything we knew about mythology, arguing that the precession of the equinoxes—a slow and majestic rocking of the Earth's axis—is the key to deciphering the oldest and most universal myths. What modern science sees as an astronomical fact, our ancestors would have seen as a great celestial machine that foretold catastrophes and golden ages.

This study invites us on a journey of discovery, revealing how myths from peoples as distant as the Norse, Greek, and Indian can be pieces of the same cosmic puzzle. In this article, we will unravel the secrets of a science common to all peoples and understand why, for Santillana and von Dechend, mythology is not fantasy, but the oldest and most fascinating form of science.

2. The Lost Science of the Ancients: The Precession of the Equinoxes

At the heart of the audacious thesis of Hamlet's Mill is the assumption that prehistoric civilizations possessed advanced knowledge of one of the Earth's most subtle and long-term movements: the precession of the equinoxes. Precession is a slow movement of the Earth's axis of rotation, comparable to the wobble of a spinning top that is losing speed. As the top spins, its tilted axis describes a great circle in space. Similarly, the Earth's axis, tilted at about 23.5°, describes a circle in the sky over a period of approximately 25,770 years. This movement causes the apparent position of the celestial pole and the location of the constellations along the ecliptic to gradually change.

Although Hipparchus of Alexandria is credited with discovering precession in 129 BC, Santillana suggests that this knowledge was known and valued by Neolithic civilizations, thousands of years before Ancient Greece. The movement is so slow that the annual displacement is less than one degree, which would have required extremely precise and systematic observations over a considerable period of time. The theory behind the work proposes that this discovery was the foundation of an "exact science" whose precision and power were later lost.

3. The Platonic Great Year and the Ages of Humanity

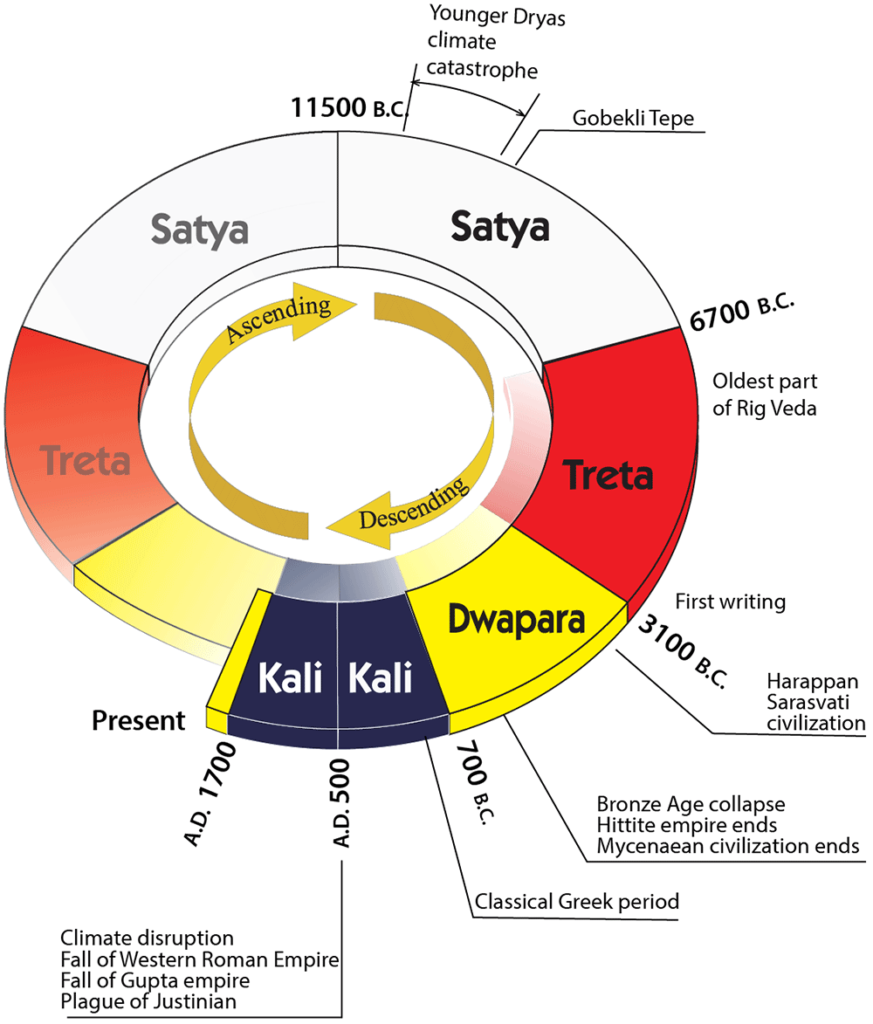

For the authors, precession was not merely an astronomical phenomenon; it was the "pacemaker" of cosmic time and the driving force behind the cycles of human civilization. They argue that the ancients viewed the precession cycle—also known as the "Great Year" or "Platonic Year"—as a force that defined the "ages of enlightenment and darkness" in human history. Precession was seen as a shift in the "structure of the cosmos," where the "great mill of heaven" became unhinged, requiring a new one to be made for a new world era.

The work suggests that the conventional historical narrative, which sees humanity evolving from a primitive to an advanced state in a linear progression, is mistaken. Instead, Hamlet's Mill proposes a cyclical view, where sophisticated scientific knowledge existed in a remote era and, instead of accumulating, "devolved" into symbolic language. This narrative of loss of knowledge and consciousness fundamentally questions the assumptions of Western science. The book suggests a deep connection between the mechanics of the cosmos and the evolution of human consciousness, an idea that resonates more with spiritualist philosophy, such as the Yuga cycles of Hinduism, than with academic history.

The authors' perception is that mythological eras, such as Saturn's Golden Age or Hamlet, were not mere fantasies, but accounts of a time when humanity was at a peak of consciousness, in tune with celestial cycles. The fall from one era to another, symbolized by the destruction of the celestial mill, is the mythical manifestation of precession, the great astronomical event that reconfigures the heavens and human consciousness.

4. Universal Myths: Hamlet, the Celestial Mill, and the Incredible Similarities

The central metaphor that unites Santillana's entire thesis is the celestial mill. According to the authors, this mill is a universal archetype that manifests in legends and folklore around the world, representing the sky rotating around the celestial pole. The celestial mill is often associated with the Milky Way and the Maelstrom, a powerful ocean current. The destruction or "unspinning" of this mill symbolizes the end of one cosmic era and the beginning of the next. The book's narrative is, at its core, a search for relics, fragments, and allusions that have survived the harsh attrition of the ages.

The hero, Hamlet, is a melancholic and intellectual figure who owns a fabulous mill. This mill had the power to grind peace and prosperity during the Golden Age, but as time waned, it switched to grinding salt and eventually fell to the bottom of the ocean. At the bottom of the sea, the mill continued to grind, but now grinding sand and rocks, creating the colossal vortex known as the Maelstrom, the "milling stream." For the authors, this legend is an allegory for the precession of the equinoxes. The Golden Age, ruled by Saturn/Hamlet, is the period of a specific celestial alignment, and the destruction of the mill and its fall into the ocean represent the shift of the celestial axis, the event that marks the end of that age and the transition to the next. The legend, therefore, becomes a codification of a fundamental astronomical event.

The strength of Hamlet's Mill lies in its comparative mythology, which seeks universal patterns in legends from different cultures. The book is a profound study that demonstrates how the same cosmic "script" repeats itself, not only in mill myths, but also in stories of floods and solar gods. Santillana and von Dechend's theory suggests that these myths are not simply a human response to nature, but an attempt to map celestial phenomena. They offer a new lens for understanding why so many civilizations, separated by oceans and millennia, seem to tell the same story.

One of the most powerful examples of this repetition is the flood myth, present in almost every great civilization. The story of a great hero who survives a cataclysmic flood to restart humanity appears in the epic of Gilgamesh, the story of Noah in the Bible, and the legend of Manu in India. In Hamlet's Mill, these floods are not just divine punishments, but the representation of an "end of a cycle." When knowledge of precession was lost, and the cosmic "mill" seemed unbalanced, it was interpreted as an apocalyptic event that destroyed the known world, allowing a new era and a new cycle of knowledge to begin. The flood, therefore, symbolizes the catastrophe that occurs when knowledge of the great celestial cycle is forgotten.

The book also explores the parallels between messianic figures and savior gods. There are striking similarities between the birth and life narratives of Jesus, Mithra, and Krishna. All are divine figures with miraculous births, associated with constellations and celestial cycles. The theory is that these "solar heroes" and "lords of the age" are actually allegories for the sun itself and for the passage of astrological ages, marked by precession. They represent the renewal of life and the return of cosmic order. This approach debunks the idea that these archetypes arose independently, suggesting that they are characters in a single grand cosmic narrative shared by all of ancient humanity.

The Mysterious Zodiac of Dendera, discovered in Egypt. Could it be a depiction of the constellations and eras? What was the purpose?

5. Facts and Mysteries: The Reception of the Thesis

The publication of Hamlet's Mill was not met with consensus in the academic community. On the contrary, the book was the subject of severe criticism and was largely ignored by the mainstream. Anthropologist Edmund Leach, in a review for The New York Review of Books, was particularly incisive, labeling the thesis of a single, global archaic civilization as "pure fantasy" and the authors' method as an "intellectual game."

Academic hostility toward the book was not only about the technical details, but also about what it represented: a fundamental opposition to the orthodoxy of evolutionary and historicist thought. Academia, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s, was firmly anchored in paradigms that viewed science as a gradual advancement and myth as a form of "primitive" thought, related to fertility rituals or agriculture. The authors, in turn, "rejected, and indeed mocked," these alternative interpretations, which contributed to the work's isolation. The book became an "outsider," not because it was entirely without merit, but because it challenged the very structure of how knowledge was validated and transmitted in academia at the time.

Despite the criticism, the work also had notable admirers. A colleague of Santillana's at MIT described the work as "an attempt to circumvent those academic gatekeepers" who prefer to ignore the connection between myth and astronomy, with the aim of "awakening public enthusiasm" for this exploration. Astrophysicist Philip Morrison, a friend of Santillana's, concluded a review for Scientific American with the phrase: "Here is a book for the wise, no matter how it may appear." This kind of praise, coming from renowned scientists, suggests that the work's value may lie in its power to inspire a new way of looking at the past and the future, rather than its scientism.

6. The Enduring Legacy: Influence and Contemporary Relevance

Despite its mixed reception in academia, the legacy of Hamlet's Mill is undeniable, especially outside conventional academic circles. The book became a "fundamental inspiration for many progressive researchers" and influenced authors exploring archaeology and alternative history, such as Graham Hancock, who dedicated an entire chapter of his book Fingerprints of the Gods to Santillana's work. This influence endures, and the book is considered the "beginning of a new way of understanding the origins of civilization" and the deep sources of ancient mythology.

The book is a "rich and interesting, but not easy to read" work. It is a "document of science as religion," in which the authors rebel against the view that reduces ancient mathematics and astronomy to "superstition" to be discarded. Instead, they seek to reclaim the reverence and value that ancient cultures placed on celestial knowledge.

Its greatest contribution is to force us to confront the possibility that knowledge, rather than accumulating linearly, can be transmitted and lost through cycles of rise and fall of human consciousness. The question of whether a common science existed, and whether myths are its fragments, remains one of the great mysteries that Hamlet's Mill left for posterity.

The boldness of its exploration has assured the book a lasting place in the history of unconventional thought and the search for the mysterious "science" that permeates our brief time here. Let us continue exploring, for after all, the truth is out there. Until next time!